A race against the clock: the efforts to save the Arapaho Language

When Patricia Goggles and Travis Shakespeare applied for the Master Apprentice program at the Wind River Tribal College to learn the Arapaho language, they were uncertain if Shakespeare would get in. After Goggles learned she was accepted into the program, excitement overcame her, but quickly she remembered that her partner was still waiting on an answer.

After their work day, Goggles urged Shakespeare to check his phone for any missed calls. A missed call from a familiar number displayed on Shakespeare’s phone screen. They knew he had been accepted. The two jumped around their living room grasping each other.

They had prayed for this.

“I think it’s an amazing journey we’re on right now,” Shakespeare said. “Getting the second chance to become people we should have become a long time ago.”

Patricia Goggles and Travis Shakespeare watch kids dance at a memorial masquerade event for a community member that recently died Oct. 21, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

At the Arapaho language’s peak in the 1940s, there were an estimated 4,000 to 5,000 fluent speakers, according to William C’hair, chairman of the Arapaho Language and Cultural Commission. Today, there are only 50 fluent speakers.

Without restoration efforts, it is estimated there will be at most 20 Indigenous languages still spoken in 2050. Before the arrival of Christopher Columbus, it is believed there were 375 distinct Native languages. After implementing a dual language program in schools on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming and the creation of a website and online dictionary, the Arapaho Tribe has seen success in exposing young people to the language.

But, an undependable dependency on technology, a hiatus in learning the language due to COVID-19 and a bottleneck generational gap that has left people hustling to learn and teach the language stunted the Arapaho language from returning in masses as some had hoped.

For Andrew Cowell, a linguistics professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, the only way to save a language is through new generations. The Arapaho Language Project began as Cowell’s dream in 2000 when he wanted to preserve the Southern Arapaho Tribe’s language.

He worked with the Tribe to create a website and online dictionary that would aid future Arapaho language teachers in learning the language themselves. Now, both the Northern Arapaho and Southern Arapaho Tribes utilize the sites.

The deterioration of the Arapaho language

Historically, the Arapaho Tribe was labeled as “peaceful.” Unlike other Tribes, when settlers came to claim the land the Tribe occupied, they did not fight back. Boarding schools and ongoing oppression left fluent speakers fearful to use their language. Many opted to not pass their knowledge to the next generation to avoid persecution and hate.

After World War II, the use of cars became more common amongst the Arapaho, according to Cowell. Before, covered wagons caused difficulty to make it into towns where English was the common language. Being active within towns and communities resulted in less use of the Arapaho language.

As technology advanced and surrounding areas became more populated, the language was disappearing.

In 1990, the Native American Languages Act legalized students to speak their tribal languages in a school setting. By then, so few were fluent. It was too late, a race against the clock to save the Arapaho language was already ticking.

“The value of the language will not be fully appreciated until it’s gone,” C’Hair said.

The Northern Arapaho Tribe

Marlin Spoonhunter, president of Wind River Tribal College was attending a Northern Arapaho ceremony nearly eight years ago when a woman was explaining what the ceremony was about in fluent Arapaho. The woman spoke for 30 seconds before looking around the room and realizing only a few understood her.

She apologized to the attendees and continued her explanation in English.

“I was sitting there and I was looking at her and I thought, ‘But our ceremonies are supposed to be spoken in Arapaho,’” Spoonhunter said. “People that are there don’t know that it’s their own fault. They don’t want to learn.”

Spoonhunter grew up speaking Arapaho while living on the Wind River Reservation, but lost touch with the language after spending nearly three decades teaching in Montana. Now, in addition to his role at Wind River Tribal College, he runs the master apprentice program. During the course of the program, apprentices are paired with two elders that facilitate their learning. The teachers will later educate new generations with the help of the Arapaho Language Project.

Marlin Spoonhunter addresses elders and other community members, describing how a typical Arapaho lesson is taught in the dual language program Oct. 21, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

Marlin Spoonhunter addresses elders and other community members, describing how a typical Arapaho lesson is taught in the dual language program Oct. 21, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

The Wind River Reservation is home to 8,600 enrolled Arapaho tribal members. Of those, only 50 are fluent in the language, the majority being elders. But, many are hopeful this decline is not permanent and believe that with effort the language can be restored.

On the Wind River Reservation, three schools have dual language programs. Right now the programs go through second grade and high school students can take the language as an elective. There are 83 students enrolled in the dual language program at the elementary school Goggles works at.

Spoonhunter now works to ensure new teachers are available to keep the language programs going by offering payment to apprentices. The expectation is that after the program they will teach in the schools.

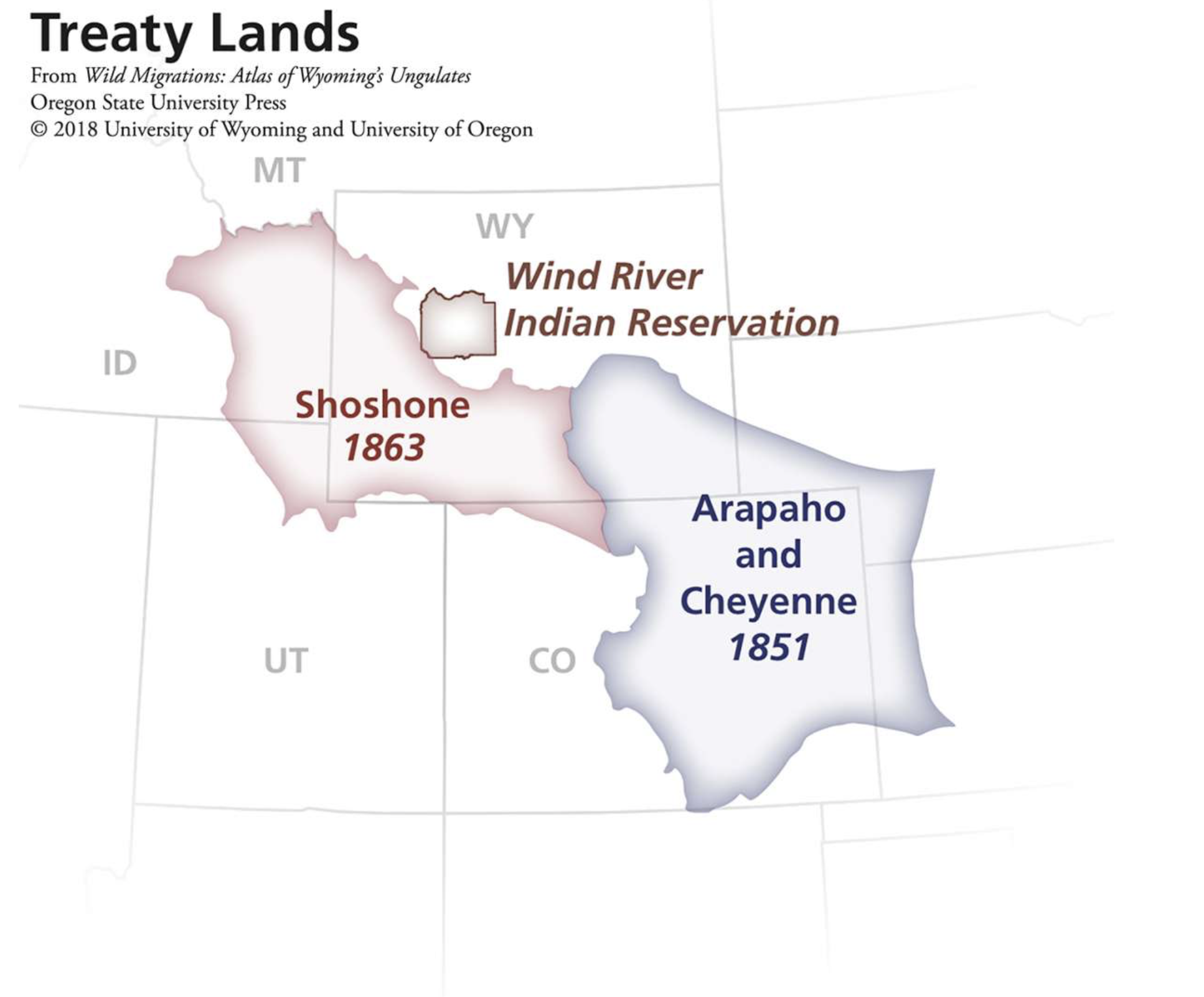

A map the Wind River Reservation today compared to the land the Arapaho Tribe used to have in the 1850s. (Map provided by University of Wyoming and University of Oregon)

A map the Wind River Reservation today compared to the land the Arapaho Tribe used to have in the 1850s. (Map provided by University of Wyoming and University of Oregon)

Cerrie White Antelope is a first grade teacher at a dual language school. She introduces one of her former students, Zendaya, to elders before they demonstrate one of their lessons Oct. 21, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

Stormee is a first grader in a dual language school. Her favorite part of learning the language is counting Oct. 21, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

Before Goggles began the master apprentice program she had one goal — say the Lord’s prayer she’s known since childhood aloud in Arapaho. For weeks she listened to the prayer on a CD. She wrote the prayer on paper and carried it with her everywhere she went.

Goggles was worried about carrying the prayer in her back pocket because apprentices are not supposed to depend on written material. With the help of an elder, Goggles was finally able to say the prayer two weeks into the program. This was the first success of what she hopes will be many, but it was a harsh reminder of historical trauma around the Arapaho language.

“There was this fear of being criticized, being laughed at and this fear of failing,” Goggles said.

Patricia Goggles asks William C’Hair for clarification on how she was pronouncing a phrase in Arapaho Oct. 21, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

Patricia Goggles asks William C’Hair for clarification on how she was pronouncing a phrase in Arapaho Oct. 21, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

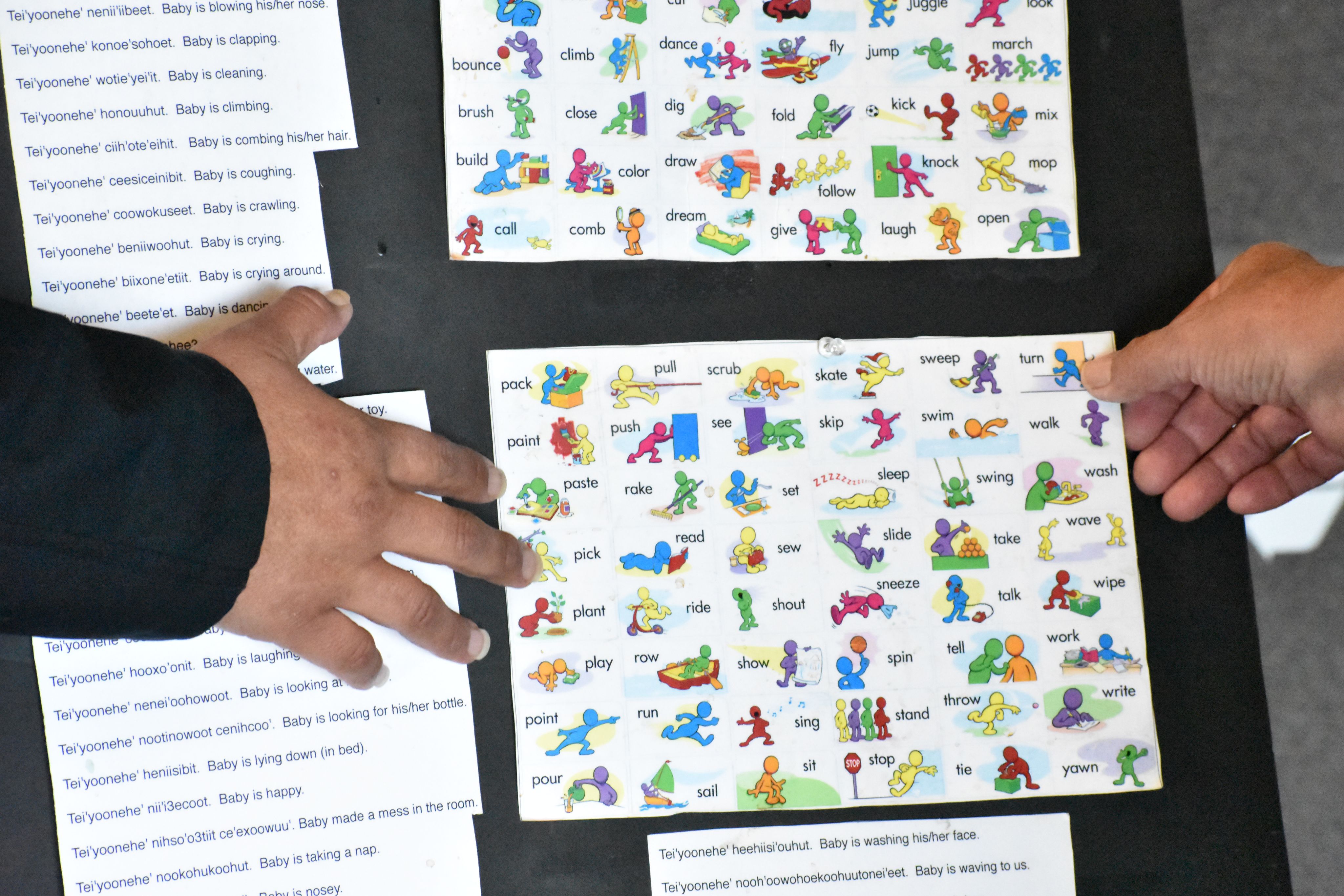

Tillie Spoonhunter and her daughter Odelie Sage are both teachers in the dual language program. They point to verbs on a board to explain a lesson they teach to William C’Hair Oct. 21, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

Tillie Spoonhunter and her daughter Odelie Sage are both teachers in the dual language program. They point to verbs on a board to explain a lesson they teach to William C’Hair Oct. 21, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

C’Hair and Spoonhunter remember the discrimination the Tribe faced. Speaking Arapaho could lead to punishment and discrimination. C’Hair remembers when it was believed by many that the Arapaho language was only grunting and tribal members could not communicate intelligently. Though Goggles and her partner Shakespeare are younger, they still carry this fear that has been passed down.

Shakespeare is set to help facilitate the most important ceremony the Tribe holds in 2026. He made a vow to learn as much of the language as he can before then. Speaking English in ceremonies has weighed on Shakespeare and made him respect elders more than he already did.

He said for tribal members, being able to connect to their culture gives them a sense of self respect. His motivation to learn the language stems from keeping the culture and language alive. Because Shakespeare is not an educator and plans to teach about the Arapaho culture and language outside of a classroom setting, he had to face a panel to be accepted into the master apprentice program.

“I told them I wanted to bring our language back into our ceremony and be able to teach and share words with people,” Shakespeare said.

A young boy participates in a drum circle at a memorial masquerade event for a community member that recently died Oct. 22, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

Apprentices in the Cheyenne Arapaho Language Project say "I am Arapaho" in Arapaho. Video was retrieved from the Cheyenne Arapaho Language Program TikTok's page.

The Southern Arapaho Tribe

James Sleeper, lead apprentice of the Cheyenne Arapaho Language Program in Oklahoma, calls out to his apprentices “hiinono'eitino',” meaning, “we are speaking Arapaho.” Sleeper gathered around a large conference room table standing above 11 seated apprentices. He had invented a new game of breaking down the word syllable by syllable, which the apprentices practiced with him before they hosted a Language Summit on Nov. 10.

After repeating, “hiinono'eitino',” the word was broken down syllable by syllable to, he-nah-nah-ay-ti-nah.

Sleeper started with “he,” Shayna Walker, another lead apprentice continued with “nah.” Amanda Goljenboom, junior apprentice, said “nah” and Ariana Yellowbank, junior apprentice, followed with “ay.” Megan Guy, junior apprentice provided the “ti” and Jeff Black, junior apprentice finished with “nah.”

This process was repeated three times until Sleeper and the other apprentices could all say together “hiinono'eitino.”

At this point in time, Sleeper is primarily focused on learning the language. However, when the apprentices are able to teach, he can feel the language coming back to life.

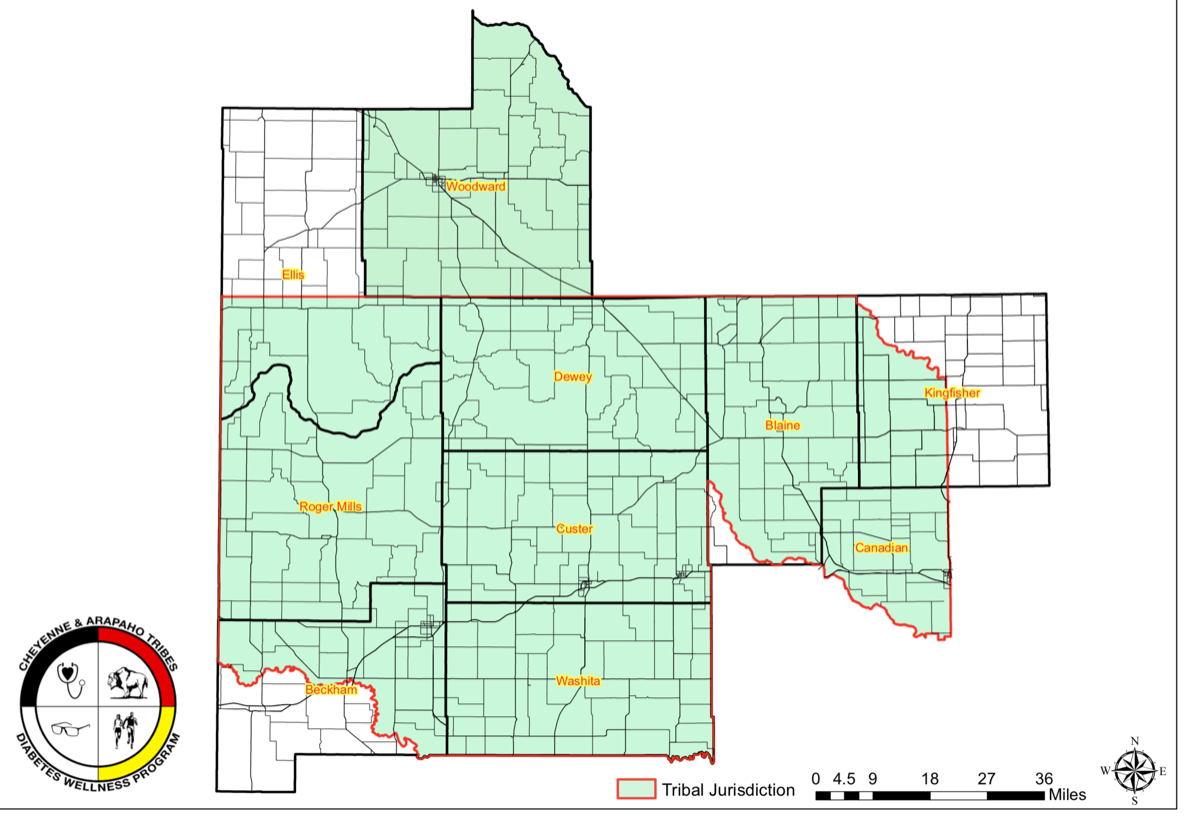

A map of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes' service areas in Oklahoma. This area extends over seven counties. Map courtesy of Shayna Walker, senior apprentice at the Cheyenne and Arapaho Language Program.

A map of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes' service areas in Oklahoma. This area extends over seven counties. Map courtesy of Shayna Walker, senior apprentice at the Cheyenne and Arapaho Language Program.

Cheyenne Arapaho Language apprentices play a game where they break down syllables to a word Nov. 4, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

“Being in schools, being in daycares and stuff like that, we’re breathing life back into our language,” Sleeper said.

The last fluent speaker in Oklahoma, Doty Lumpmouth Jr., died in 2016, leaving tribal members there to rely on learning through the Arapaho Language Project developed by Cowell and weekly Zoom meetings with fluent elders in Wyoming.

The explanation for that present day challenge has deep and dark roots. After the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864, the Tribe was split in two. The Southern Arapaho were moved onto a reservation with the Southern Cheyenne Tribe. Now, the Tribes are recognized as the combined Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes. The total number of enrolled tribal members in Oklahoma is 8,664, but it is unclear how many are solely Southern Arapaho.

The apprentices agree that consolidating the tribes helps gain federal recognition. Otherwise, it is uncertain the Southern Arapaho would be recognized.

Again, the past underscores the need for such recognition, but the results have long been mixed and troubling. After the Tribes were combined and given reservation space, former President Benjamin Harrison opened 1.9 million acres of Indian Country to white settlers, most of which was in present day Oklahoma. In what became known as the Land Run, on April 22, 1889, at noon, thousands of settlers traveled to Oklahoma. The surge of land-seekers resulted in a checkerboard reservation, separating tribal members.

Each Native family was allotted 160 acres of land. Many still live with their families on the same land, including Billie Sutton, one of the first apprentices in the Cheyenne Arapaho Language Program.

The result of that separation, and the passing away of elders in Oklahoma following efforts to force children to discard their native language, has put a strain on maintaining their culture. Sutton believes that the Arapaho language brings the community together.

“When they had the land run, we no longer really had a reservation, a real reservation, where we were altogether in a community,” Sutton said. “You had native families, white families, native families, etc. We just weren’t together.”

Before Sutton became a language advocate she taught for 27 years at a technology center. In 2013, she was hired on to the Cheyenne Arapaho Language Project as a curriculum specialist. She developed an Arapaho curriculum for high school students, but it was never implemented.

“We did it backwards, we got the curriculum, but we didn’t have the teachers,” Sutton said.

Sleeper joined Sutton in the program in 2013 when Rebecca Kisenhoover, director of the apprentice program, started overseeing them. Sleeper had started learning the basics of the language on his own a few years prior, opting to learn the language exclusively through oral practice. Now, he acts as the official lead apprentice for the program.

Sleeper and Sutton had fundamental differences for how they wanted the program to be, causing Sutton to step back in her role. She eventually left in 2017, when her commute of over an hour became too much. The program has grown since with the addition of junior apprentices, but continues to be the only program in Oklahoma.

Kisenhoover would like to see the program result in a bachelor’s degree, allowing apprentices to teach in schools. Sleeper is hesitant to this idea though. For him, learning to speak is more important than teaching.

The Cheyenne Arapaho Language apprentices work through a Department of Education building that was formerly a boarding school Nov. 4, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

There has been criticism from both the Northern and Southern Arapaho Tribes about how the Cheyenne Arapaho Language apprentices are learning the language, because of their utilization of the Northern Arapaho Tribe. Subtle dialect differences between the two are important to some, but not to others.

“If somebody in Oklahoma sees an elephant, the word for it is ‘it has a long nose,” Sleeper said. “Somebody from Wyoming sees it, they say ‘it has big ears.’ If you don’t know the language, you are going to say ‘Oh they are talking Northern and they are talking Southern,’ but that’s not true, they are speaking the same language.”

Walker feels nervous speaking in Arapaho in front of members from the Northern Arapaho Tribe. When she hears them speak, she can hear the dialectic differences.

“They sounded so much better than us, they just have that sound, I don’t know what it is, but it sounds really pretty. We don’t have it,” Walker said.

Without constant and consistent access to elders, the apprentices do not have the means or the knowledge to create immersion schools. The apprentices hope they can become comfortable enough with the language to pass it on to their children, making a new wave of first language speakers.

“Teaching is really secondary for the majority of us here,” Sleeper said, “We are at a disadvantage because we are not fluent speakers. So in Wyoming they have immersion schools where they work with preschool aged kids and they have fluent speakers there working, but over here, we’re just now preparing these apprentices here to be those types of people.”

An abandoned boarding school in Canton, Oklahoma resides near Canton Dam. Billie Sutton believes there are remains of Southern Arapaho people there. “Wherever there is a boarding school I believe there will be graves,” she said Nov. 5, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

A cemetery in Canton, Oklahoma, where Billie Sutton lives, is filled with several Southern Arapaho Tribal members that were moved when Canton Dam was built in the 1940s. Nov. 5, 2022. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

Technology’s role

When Cowell started the Arapaho Language Project, he saw the potential technology had. Apprentices and teachers saw it too. But, a few years ago, the University of Colorado Boulder requested Cowell to switch servers for the project’s website.

According to Cowell, the university claims the original website was not accessible because it lacked enough English and had too many recordings unaccompanied with writing. As well, the university wanted the site to have more of the university’s branding such as its colors and logos. However, when the site was being created, the Northern Arapaho Tribe worked with Cowell and requested specific colors and the Tribe’s flag be integrated throughout.

When the new site was made, it became harder to find and access. The online dictionary Cowell made to accompany the site faced the same struggle.

“There were a couple of times I couldn’t find (the dictionary),” Spoonhunter said. “And I talked to some of the teachers, they kind of said the same thing, ‘Oh, we couldn’t find it.’ But, then it was said it was down for a while.”

In 2018, the university decommissioned a server from the 1990s. For nearly nine months the university’s Office of Information Technology worked with staff through the transition. According to Andrew Sorenson, spokesperson for the University of Colorado Boulder, the Linguistics Department is in the process of updating the project’s old site and has requested it be pulled down meanwhile.

“CU Boulder understands the importance of preserving Native languages and supports those goals,” Sorenson said.

The university did not comment on the lack of accessibility claims Cowell discussed.

Sutton believes that technology is crucial to learning Arapaho. Oral recordings are essential because of the tonal makeup of the language.

“We’ve got to hear it, and in my case, in my community where I live, there is nobody. There is nobody to learn from, nobody to talk to,” Sutton said.

One way the Cheyenne Arapaho Language Program is trying to combat the distance between tribal members in Oklahoma is by developing an app. Zach Rice was hired last November to help develop the app where tribal members can access recordings of Arapaho and Cheyenne from elders. Rice believes the app will be ready for use in December.

“All of our speakers are in Wyoming and we’re in Oklahoma, so that’s about an 18-hour difference or 16-hour difference depending on how (far) you drive,” Sleeper said, “Over the past six years that we have been doing this, probably 90% of the time has been over Zoom, even before COVID.”

COVID-19 led to a hiatus in learning Arapaho, but proved technology’s strength

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Indigenous communities were hit at alarming rates. Cowell was unable to make visits to the Wind River Reservation for months. Simultaneously, in-person learning was paused. The lack of online resources led to a hiatus in learning.

In Oklahoma, they were unable to meet and practice for eight months. During this time they were not able to work with Cowell, and their weekly Zoom meetings with the elders were put on pause. While this time was filled with anxiety and fear, according to Walker, she believes the strife of the pandemic reminded them of the importance of their language.

“We were calling and checking on our speakers too, there were elders and we lost a lot of tribal members and tribal elders,” Walker said, “I think some of that needed to happen because it pushed us back into wanting to get everything started again, and we’ve seen how important our language is.”

Spoonhunter said learners heavily depended on tribal elder’s knowledge during this time. When COVID-19 vaccines were made available, fluent tribal elders were the first to receive them because of their knowledge of Arapaho and ceremonies, according to Cowell.

Billie Sutton drives around Canton, Oklahoma, part of the checkerboard Arapaho reservation on Nov. 5, 2022. Sutton used to drive more than an hour to participate in the Cheyenne Arapaho Language Program before the commute became too much for her. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

Billie Sutton drives around Canton, Oklahoma, part of the checkerboard Arapaho reservation on Nov. 5, 2022. Sutton used to drive more than an hour to participate in the Cheyenne Arapaho Language Program before the commute became too much for her. (Zoe Schacht/CU News Corps)

A generational gap has fueled the urgency to learn

A primary struggle for teachers and learners is what Cowell calls a bottleneck generational gap. Elders who are fluent in the language did not pass their knowledge on to their children and the language was lost overtime. But, children pick up the language at a quick rate. By the time students have been learning for six months, they have caught up to their teachers, Cowell said.

However, many lack true desire and care to learn Arapaho. Spoonhunter said, learners have to take significant time practicing both in and out of the classroom to see improvement, but rarely does he actually see this happen.

“A lot of people don’t realize the urgency because a lot of them aren’t learning the language. They’re mainly English speakers. There’s an attitude about, ‘what’s the language going to do for me? Is it going to give me a job?’” Spoonhunter said.

Sutton has experienced the generational gap firsthand within her family. Her grandparents spoke the language fluently, however they refused to teach their children or grandchildren. If Sutton asked how to say a specific phrase or word, they would tell her, but they would not actively teach her the language.

“They wouldn’t speak it or teach us. They said they didn’t want their kids to learn because their kids had to go to public school and they wanted their children to do well in public schools,” Sutton said.

The term fluency implies a complete mastery and understanding of the language. However, Cowell believes that the term is actually quite fuzzy.

“The ability to speak at a normal conversational pace without stumbling or searching for words on pretty much any topic, would be one definition of fluency,” Cowell said.

Cowell believes that the goal of “fluency” might actually serve as a deterrent from people trying to learn the language. This is because people just beginning to learn the language find that fluency is too daunting. Cowell believes we should shift the focus from fluency to productivity.

“So if we think more about just productivity, and do you know the language well enough to invent a new sentence on your own or a new song on your own,” Cowell said, “You’re able to do something really good, you’re not just dependent on memorizing stuff and that kind of takes the pressure off.”

For Sutton, fluency is a sliding scale. She currently believes she is at the speaking level of a toddler, but continues to go to the weekly Zoom meetings with elders, reach out to Cowell, and make videos about learning Arapaho, all to be more connected with her language.

“We’re learning and we’re going to be learning for the rest of our lives, that’s just all there is to it,” Sutton said.