A Citizen Historian Reveals Another Window to Estes Park

Escaping from the sweltering summer heat of their home of Borrego Springs, Calif., Nancy Burke and Oscar Ødegaard set their sights toward the Rocky Mountains for their yearly adventure. Given their destination was Estes Park, Burke and Ødegaard decided to name their latest recreational trailer after Isabella Bird, a British explorer known for her 1873 trip to the Colorado Territory, and who later compiled a book about her experiences called “A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains.”

One Saturday afternoon as they were exploring the downtown, Burke spied a shop on Moraine Avenue that she knew Ødegaard, a history buff in his own right, might like: “Ten Letters” owned by John Meissner—a local historian who sells a variety of archival prints of Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, as well as souvenirs and other knick-knacks.

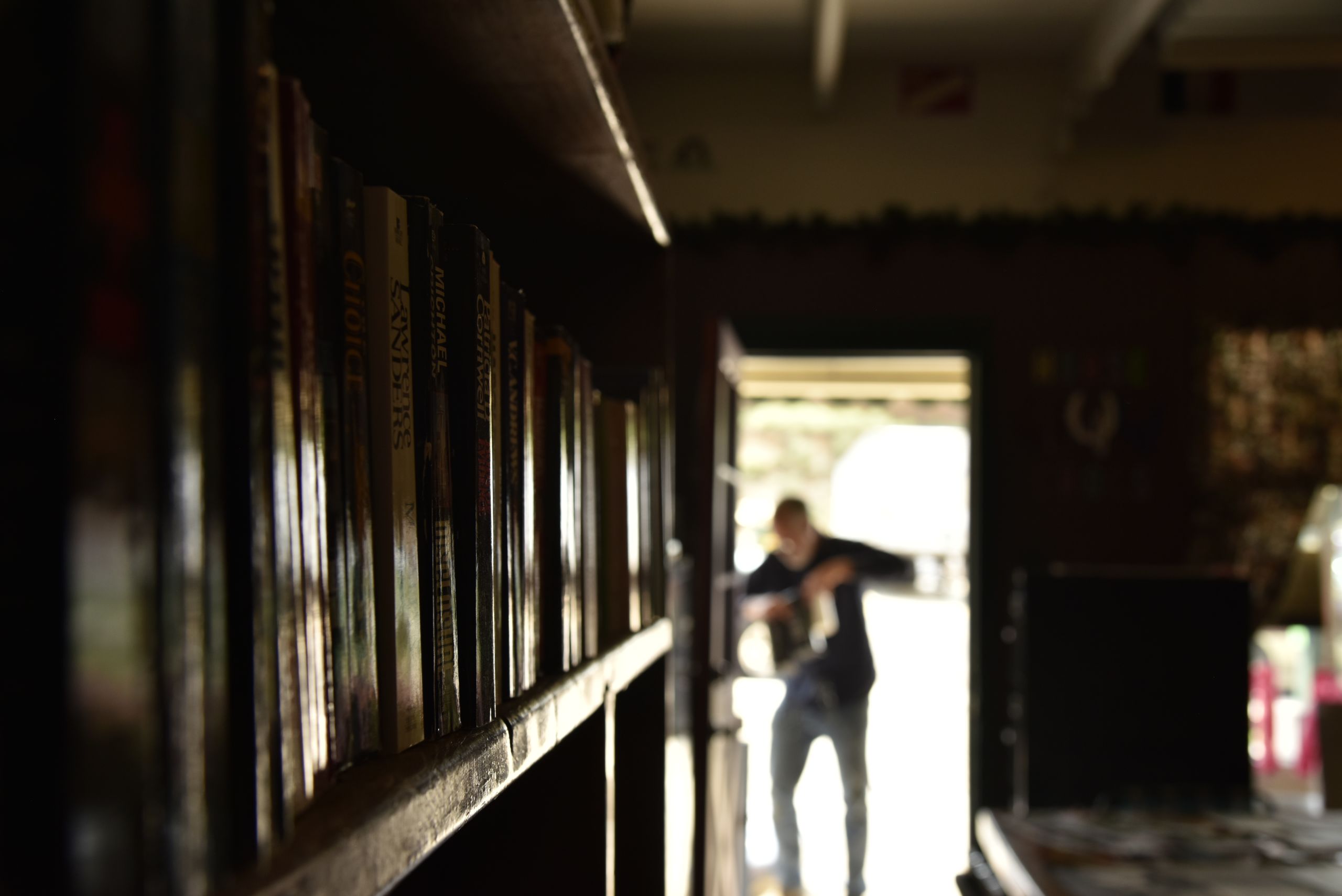

Meissner in his store "Ten Letters" on Moraine Avenue near downtown Estes Park on July 10, 2021. Along with selling archival prints of Estes Park, Meissner holds history seminars on Saturday evenings during the summer. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

Meissner in his store "Ten Letters" on Moraine Avenue near downtown Estes Park on July 10, 2021. Along with selling archival prints of Estes Park, Meissner holds history seminars on Saturday evenings during the summer. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

“Ten Letters” sits just up the road from the bustling summer tourist crowds at the intersection of Moraine and Elkhorn Avenues in Estes Park, within sight of one of the town’s most prominent landmarks: the Park Theatre. When he isn’t at his shop, Meissner might be found occupying an outside table just down the street at MollyB Restaurant. With a coffee in hand, Meissner explains—possibly to anyone who will listen—the stories of this mountain town and the gateway to one of the crown jewels of the National Park System, Rocky Mountain National Park.

“We walked inside John's store and, to our surprise, discovered that he was offering a history lecture that evening,” Burke said. “Then he and Oscar chatted for two hours straight.”

***

Alternative historian to some and resident gadfly to others, Meissner is probably best described as a storyteller whose observations and criticisms of his beloved home are a departure from the often anodyne historical orthodoxy found in most Estes Park tourist pamphlets.

To most visitors, Estes Park is most famous for its proximity to Rocky Mountain National Park and as the home of the Stanley Hotel, a 142-room Colonial Revival structure built in 1909 by Freelan Oscar (F.O.) Stanley as a retreat for wealthy East coast visitors and for sufferers of tuberculosis.

But Meissner possesses an almost encyclopedic knowledge of the history of area. While not a historian by trade, his background as virology researcher, a collector and a numismatist inform his status as a “citizen historian.”

However, it’s his deep familial ties that connect Meissner to Estes Park. Just like the historical figures that he researches so intently were astounded by the beauty and potential of this valley, Meissner felt the same pull in spite of a career that took him around the globe. His maternal grandparents first constructed a cabin in the 1930s near what is now the Beaver Meadows Visitor Center at the entrance to Rocky Mountain National Park. Later, his parents would bring both Meissner and his sister to Estes Park in both the summer and the winter months to a house they built just a short distance away from the former site of his grandparents’ cabin.

“I was traveling around the country and overseas in Russia doing all this work for virology, but during my downtime I’d come back,” Meissner said. He started to explore more of the town’s history, but it was a coin shop on Moraine Avenue that piqued his curiosity. He wanted to find out the origins of the shop, and he discovered a lot of roadblocks to his research along the way.

Meissner closing up his shop in Estes Park at the end of the day on July 10, 2021. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Meissner closing up his shop in Estes Park at the end of the day on July 10, 2021. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Meissner describes the history of development in Estes Park through a map of the town on July 3, 2021. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

Meissner describes the history of development in Estes Park through a map of the town on July 3, 2021. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

Meissner speaks with Estes Park residents Donna and Jake Meyer before his weekly meeting to talk about the history of Estes Park on July 10, 2021. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Meissner speaks with Estes Park residents Donna and Jake Meyer before his weekly meeting to talk about the history of Estes Park on July 10, 2021. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Meissner hosts a weekly meeting in his store to talk about the history of Estes Park with Nancy Burke and Oscar Ødegaard, Jake and Donna Meyer, and Sybil Barnes, the former Estes Park history librarian on July 10, 2021. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

Meissner hosts a weekly meeting in his store to talk about the history of Estes Park with Nancy Burke and Oscar Ødegaard, Jake and Donna Meyer, and Sybil Barnes, the former Estes Park history librarian on July 10, 2021. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

Local tourists Tanner Miller and Maci Ames of Loveland eat outside Penelope's Hamburger & Fries in downtown Estes Park on July 10, 2021. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Local tourists Tanner Miller and Maci Ames of Loveland eat outside Penelope's Hamburger & Fries in downtown Estes Park on July 10, 2021. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

A group poses for a picture on the Estes Park Riverwalk, which abuts the Big Thompson, one of two rivers flowing through Estes Park on July 3, 2021. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

A group poses for a picture on the Estes Park Riverwalk, which abuts the Big Thompson, one of two rivers flowing through Estes Park on July 3, 2021. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Weekend crowds in Estes Park cross at the intersection of Elkhorn Ave., and Big Horn Dr., also known as "the Corners" on July 3, 2021. Traffic cops take over for the stoplights to mitigate issues between busy pedestrian sidewalks and vehicles on the street. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Weekend crowds in Estes Park cross at the intersection of Elkhorn Ave., and Big Horn Dr., also known as "the Corners" on July 3, 2021. Traffic cops take over for the stoplights to mitigate issues between busy pedestrian sidewalks and vehicles on the street. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Dan Adkins, and his son Aaron, from Council Bluffs, Iowa, have a quiet moment on river on July 10, 2021. The Adkins spent a week exploring Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Dan Adkins, and his son Aaron, from Council Bluffs, Iowa, have a quiet moment on river on July 10, 2021. The Adkins spent a week exploring Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Park Theatre, the oldest single house theater in Estes Park still operating on July 10, 2021. Built in 1913, this historic landmark is on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Park Theatre, the oldest single house theater in Estes Park still operating on July 10, 2021. Built in 1913, this historic landmark is on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

“It was frustrating because I couldn’t get any of that information from any local sources. Instead I was in Colorado Springs looking through old newspapers and magazines,” Meissner said, adding: “If this is so hard, it’s obviously hard for anyone to research their family or their cabin or anything else.” And so began his deep dive into the history of the area, filling in what he perceived as gaps with primary sources such as newspaper articles, letters and stories from the characters that color the town's early days.

The best way these stories emerge is through an impromptu walking tour of downtown with the town's citizen historian.

Meissner explaining the history of Estes Park and its relationship to the Big Thompson River on July 3, 2021. Early tourists fished upstream of the town; the river that flowed through the town itself was often fouled by waste from hotels and businesses, until environmental regulations in the 20th century halted those activities. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

Meissner explaining the history of Estes Park and its relationship to the Big Thompson River on July 3, 2021. Early tourists fished upstream of the town; the river that flowed through the town itself was often fouled by waste from hotels and businesses, until environmental regulations in the 20th century halted those activities. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

The continuous river of tourists that flow up and down the street dodge his gestures (Meissner likes to speak with his hands) as he pauses to explain the significance of a building at the corner of Elkhorn Avenue and Big Horn Drive.

“The bank was started in 1908 with funds from F.O. Stanley, in addition to some local people on the board,” he begins.

The former bank now houses a Nepali and Indian restaurant, a glass-blowing studio, a confectionery shop, and one of Estes Park’s ubiquitous T-shirt stores.

Meissner points to a plaque affixed next to the window of the glass-blowing studio. These plaques were commissioned in 1992 by the Estes Park Museum in conjunction with the 75th anniversary of the town’s incorporation.

He explains the positions of a few individuals listed on the plaque who served as the bank’s manager, and then begins to editorialize slightly: “regardless of what any of this says” —he gestures to the plaque again— “this is F.O. Stanley’s money that’s deposited and keeping this thing solvent.”

At the Riverwalk along the Fall River, Meissner describes the former location of the Dark Horse Saloon in Estes Park on July 3, 2021. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

At the Riverwalk along the Fall River, Meissner describes the former location of the Dark Horse Saloon in Estes Park on July 3, 2021. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

The walking tour takes a circuitous route past more plaques on Elkhorn. At the Village Goldsmith shop, near where the Fall River runs under West Elkhorn Avenue and, on two major occasions has caused devastating flooding to downtown Estes Park, Meissner pops his head inside to see if the former mayor is working. (Not today, says a salesperson.) Winding down along the town's Riverwalk, Meissner notes a few lesser-known facts that aren’t necessarily found such as why all of Estes’s downtown structures face away from the two major rivers that flow through the town: the Fall and the Big Thompson River.

“No one in the late 19th century really cared about the river; hotels and businesses downtown were happy to use it as their own personal sewer system and trash collector,” Meissner explains.

At the entrance of the Park Theatre, he references the building’s historical plaque and provides his own analysis of when the tower was built. “The theater tower was built in 1929. There are pictures from 1927 that don’t have the tower and there’s no mention in our newspapers about building the tower that early.”

Meissner explains the writing on a plaque detailing the history of the Park Theatre on July 3, 2021. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

Meissner explains the writing on a plaque detailing the history of the Park Theatre on July 3, 2021. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

Referring once again to the tower, Meissner says: “This is our landmark; this is our milepost; this is where everything from Estes Park is measured and that we get that accurate.”

***

Meissner admits that he gets in trouble with some of the town’s historians when it comes to details, ranging from the minute (dates on plaques) to the significant, such as what he describes as the top ten “holy grail” primary artifacts and documents from Estes Park’s history. In fact, it’s the primary documents that drive his understanding and his desire to explore the foundational history of Estes Park—the good, the bad, and the ugly.

His background as a virologist plays a significant role in informing his research. Meissner used to model how amino acids help build different proteins in viruses; he applies similar research techniques to track down important dates, such as pinpointing the location of Windham Wyndham-Quin, the 4th Earl of Dunraven in a given year.

Just as the Arapaho people who had hunted, trapped and camped in the area long before him, the British earl played an important role in Estes Park history. Seeing the value of the area as a tourist destination—albeit, perhaps only for big game hunters— he secured 15,000 acres for himself.

A walking tour of downtown can quickly turn into a driving tour, as Meissner points out various sites and landmarks: the lodge where the 4th Earl of Dunraven might have stayed during his first summer; the approximate location from which the artist Albert Bierstadt stood to paint his famous landscape of Longs Peak; and the former entrance to Rocky Mountain National Park along the Big Thompson River, before the National Park Service’s Mission 66 program created the Beaver Meadows entrance along with its visitor center designed by the architecture firm founded by Frank Lloyd Wright.

And just up the road from the Beaver Meadows Visitor Center, the former location of a vacation cabin owned by Meissner’s grandparents.

Meissner's grandparents and his mother pose on the porch of their Estes Park summer cabin. The site is now located within National Park boundaries. (Photo courtesy of John Meissner)

Meissner's grandparents and his mother pose on the porch of their Estes Park summer cabin. The site is now located within National Park boundaries. (Photo courtesy of John Meissner)

On Saturday evenings during the summer season, Meissner clears off the large oval dining table that sits inside his shop. Yellowed maps, black-and-white photographic reprints, history books and other ephemera from Estes Park’s past are pushed to the corners. A stack of handouts await any guests who decide to show up, and tonight there are five: Donna and Jake Meyer, two Estes Park history enthusiasts; Sybil Barnes, the former Estes Park history librarian; along with Burke and Ødegaard.

The subject of Meissner’s lecture? An historical analysis of Isabella Bird’s book, making Burke and Ødegaard's journey to Estes Park all the more serendipitous. Meissner lent Ødegaard his copy of Bird’s book for homework in preparation for his lecture.

Meissner and his five guests pore over photocopied handouts of Union Pacific timetables, newspaper clippings, and mileage estimates in an attempt to determine when Bird arrived in Colorado. A gap in the timeline between Bird’s arrival in Salt Lake City and her journey to Laramie prompts a discussion. Could it have been a rest day, or perhaps Bird simply forgot to make a note of it in her diary? Burke suggests that, perhaps, Bird was the victim of theft or even a more sinister misfortune. Based on her understanding of Bird, it’s possible that the explorer’s self-image and desire to self-promote caused her to omit that day from her records—the 19th century version of curating oneself for the media. The discussion is part forensic analysis, part literary debate, and part history lesson.

About halfway through the discussion, the door to the shop bursts open and a small boy storms in with a cheeseburger and fries on a plate—Meissner’s dinner from MollyB’s.

“John, here’s your dinner!” the boy says. "Are you done talking yet?”

Smiling at the interruption, Meissner thanks him and ushers him out the door. Wrapping up the conversation, Meissner explains that next week’s discussion will continue with Isabella Bird’s story, including her encounter with another Estes Park legend James “Rocky Mountain Jim” Nugent and her ascent of Longs Peak.

A comparison of Longs Peak over time. The upper photo is by Albert Bierstadt, a 19th century landscape painter. The lower photo is the mountain today, taken on July 17, 2021. Meissner says Bierstadt tried to make Longs Peak look like a towering, 19,000 foot mountain that belonged in the Alps. The most accurate USGS survey puts Longs Peak at 14,259 feet. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

A comparison of Longs Peak over time. The upper photo is by Albert Bierstadt, a 19th century landscape painter. The lower photo is the mountain today, taken on July 17, 2021. Meissner says Bierstadt tried to make Longs Peak look like a towering, 19,000 foot mountain that belonged in the Alps. The most accurate USGS survey puts Longs Peak at 14,259 feet. (Zain Alexander Iqbal, CU News Corps)

Ødegaard lingers for a while, talking to Meissner. They head out into the cool evening air and take a seat together on two stone benches facing Prospect Mountain. Burke sits on a metal picnic bench nearby and weaves the connection between their newfound knowledge of Isabella Bird to their travels.

“We discovered an elementary school near Aurora named after her, discovered she was a big deal in Denver, and came up to Estes to learn even more about her. We walked into John’s shop and he made us feel very welcome.”

“Exploring history,” Burke said, “is what Oscar and I do.”

***

Ask Meissner what gives Estes Park and its unique natural environs a sense of place, and he will tell you, naturally, to look at the town’s history. Over a coffee at MollyB, an endless stream of tourists and traffic continues to flow by on Moraine Avenue. Meissner makes an impassioned plea for the town to recover and display those “holy grail” artifacts and primary sources that he feels are critical to illuminating the town’s early history.

His wish list includes recovering original sketches or paintings of the area by Valentine Bromley, the British artist who illustrated the 4th Earl of Dunraven’s book, “The Great Divide,” a copy of the St. Vrain Hotel register from 1873, or cattle brands used by the pioneer and ranch Griffith Evans. Not one to shy away from the darker side of Estes Park history, Meissner would also like to see the membership rolls of the local Ku Klux Klan chapter from the turn of the 20th century.

During a walking tour, Meissner explains how the land near what is now downtown Estes Park was surveyed by the 4th Earl of Dunraven at the "Corners" — the intersection of Elkhorn Avenue and Big Horn Drive on July 3, 2021. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

During a walking tour, Meissner explains how the land near what is now downtown Estes Park was surveyed by the 4th Earl of Dunraven at the "Corners" — the intersection of Elkhorn Avenue and Big Horn Drive on July 3, 2021. (Warren Vause, CU News Corps)

“I want this to serve as a town repository for everyone to look at and say ‘holy cow, Estes Park had a fascinating and intriguing early history.’” Meissner said. “Just like Denver, Colorado Springs, and all these other communities, we were a player back at that time and we had major artists and authors visiting here and falling in love with it.”

He adds, “With Isabella Bird, she’s our first public relations person, and even with the 4th Earl of Dunraven it was all about tourism. It was about attracting people to come up to enjoy what he enjoyed.”

***

At the end of the tour, Meissner drives up to the former site of his grandparents’ cabin just across Rocky Mountain National Park boundary. At a large rock nestled under a cluster of ponderosa pines, Meissner offers insight into his own family’s history—a history that explains how Meissner interprets his own sense of place in Estes Park.

He gestures toward a shaded rise in the landscape and explains how his grandparents came out from Nebraska and built their rustic cabin in a neighborhood within sight of the grandeur of the Continental Divide.

Even though the neighborhood is long gone, Meissner would like to gather historical photographs from the families whose ancestors discovered for themselves the unique pull Estes Park has on visitors, and who ended up making it their permanent vacation spot.

"With some pictures, we could give this (neighborhood) some life." Meissner says. “It’s harder the longer you wait, so I should stop talking about it and start doing it.”