Older Colorado Prisoners Face Extreme Risk from COVID-19

Hundreds of the state's most vulnerable languish in human-made hot zones.

Kimberly Matteo reads a letter her brother Kevin Bretz wrote for fellow inmate Anthony Martinez's niece Kelly Braiser.

It is 5 a.m., and Kelly Brasier wakes to the sound of her alarm clock. The wooden floors of her home creak as she heads to the kitchen for a cup of tea, making each footstep sound pronounced and forlorn. As she waits for the water to boil, she thinks about her Uncle Anthony and fights back tears.

Kelly Brasier at her Pennsylvania home. (Photo courtesy Cody Brasier)

Kelly Brasier at her Pennsylvania home. (Photo courtesy Cody Brasier)

Brasier rises this early every day so that she can be ready should her uncle call.

Anthony Martinez is incarcerated in Sterling Correctional Facility on the eastern plains, where repeated outbreaks of COVID-19 have endangered the lives of hundreds of inmates. Sterling is not alone: Many of Colorado’s prisons have experienced huge problems containing the spread of the virus inside their walls.

Kelly’s fears for her uncle’s safety are certainly warranted. As the virus rages around him, he is going nowhere. In 1989, he was convicted of a string of robberies under a habitual offender law that basically saddled him with a life sentence. While Martinez is eligible for parole in 2025, he is 84 years old, wheelchair-bound, nearly blind and deaf, and now in the initial stages of renal failure.

Martinez is one of over 1,200 Colorado prison inmates older than 60. Their age and incarceration in what are essentially COVID-19 hot zones place them at extreme risk from the virus. Against this backdrop, prison officials struggle to find an equitable solution. The state appears to be paralyzed about how to proceed — even though the danger is likely to last.

Ever since Martinez’s incarceration, Brasier has been fighting to bring him home. She has written hundreds of letters to Colorado governors and Department of Corrections officials imploring that her uncle be freed to live out his remaining years under her care. Several years ago, she outfitted a room on the ground floor of her home in Farrell, Pennsylvania with a hospital bed in anticipation of his return.

When COVID-19 started to sweep through Colorado’s prisons, Brasier became desperate.

“I’m scared because of his age and of his various health issues that he may not make it out of prison alive,” she said. “If he doesn’t die of health-related complications, the virus will definitely kill him if he contracts it at his age with his health issues. He only has a few years left. He should be able to live out the remainder of his life with his family.”

Martinez fears for his safety as well. His descriptions of conditions inside Sterling keep Brasier on edge.

"I feel like I've been put up against the wall and shot."

“I feel that the staff has been negligent in its duty to keep us in a safe environment,” wrote Martinez in a letter to the ACLU of Colorado. “Constantly moving us multiple times into housing areas with people whose roommates just tested positive and without proper sanitation of the cell or quarantine of the exposed inmate. For me, this can be a potential death sentence, at my age of 84.”

Since the onset of the pandemic, outbreaks of COVID-19 have erupted in dozens of prisons all over the state. “This is a real reckoning, because all the biggest outbreaks in Colorado were in prisons,” said Helen Griffiths, public policy associate for the ACLU of Colorado. Four of the ten largest COVID-19 outbreaks in the state have been in correctional facilities. The largest and deadliest blazed through Sterling in June and July, infecting over 600 inmates and killing three.

Among inmates in the state’s prisons there have been at least 972 cases of COVID-19 and at least three deaths.

To be locked down in a hotbed of infection is especially distressing for Martinez and others of the 1,237 prison inmates in Colorado older than 60, who face a heightened risk of serious health complications or death from COVID-19.

Emergency equipment on standby. (Photo courtesy an anonymous source)

Emergency equipment on standby. (Photo courtesy an anonymous source)

“Older people are the fastest-growing population in Colorado’s prisons, and that’s really concerning because older people are also who are more vulnerable to COVID,” said Griffiths.

While prison inmates older than 60 are more likely to develop complications from COVID-19, they also have a heavier burden of chronic illness than does the general population.

“This intersection of age and heavy burden of chronic illness puts older people who are incarcerated at extreme risk,” said Lauren Brinkley-Rubinstein, a professor of social medicine at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill currently researching the effects of COVID-19 in prisons.

Incarcerated people in general have higher rates of underlying health conditions, including HIV, tuberculosis and diabetes, that place them at greater risk of complications from coronavirus.

The Colorado Department of Corrections has taken steps on several fronts to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in its prisons, a testament to Colorado seeing fewer cases among inmates than 25 other states and fewer deaths than 30 other states.

“At Sterling, we’re testing [inmates] once a week, and at other places once a month,” said Rick Thompkins, chief human resources officer for the Department, in a remote Citizens’ Advocate Meeting on Oct. 8.

The Department conducts mandatory point-prevalence survey testing for staff at all prison facilities. (Point-prevalence survey tests a group of individuals at a single time, e.g., on one day or over two days.)

“Staff can drive through, be tested, and be notified confidentially of their test results,” said Thompkins.

Centennial South Correctional Facility, shuttered in 2010, was reopened in March for use as the state’s sole intake facility for all inmates. “They stay at Centennial for 14 days and we administer extensive COVID tests,” said Matthew Hansen, the Department’s deputy director of prisons, in the Oct. 8 meeting.

The Department also uses technology to facilitate social distancing. “We’ve moved to more virtual training, so we lessen the interaction of our employees where they might possibly spread the virus,” said Thompkins.

Colorado’s cities and counties have freed a substantial number of inmates from jails in an effort to reduce population density and stem the risk of an outbreak. According to a report published this month by the ACLU of Colorado, jail populations in the state dropped by 46% from March to June. The ACLU projects this will save the state some $210 million a year if population levels remain low. The Department has also halted the transfer of people who would normally move from jail to prison after sentencing.

Jails typically house low-level offenders, as well as those awaiting trial. Only convicted felons are sent to prison.

Colorado’s prison population dropped by only 12% from March to June. The Department has been warier of releasing prison inmates, who could be much more dangerous — like Kevin Bretz, a 63-year-old, 400-lbs inmate at Sterling who requires oxygen and sleeps in his wheelchair. Bretz is an aspiring artist serving a 96-year sentence for crimes including first degree assault. He could be released at the earliest in 2079.

Kevin Bretz photo of Kimberly Matteo. (Carlos Monkus, CU News Corps)

Kevin Bretz photo of Kimberly Matteo. (Carlos Monkus, CU News Corps)

Last month Bretz fell out of his chair during the night and lay helpless on the cold, concrete floor of his cell until morning, when three correctional officers were needed to lift him.

“My brother isn’t a risk to society,” said Kimberly Mateo, sister of Bretz. “He can’t even get off the floor. How is that a risk?”

Kimberly visiting Kevin before the pandemic. (Photo courtesy Kimberly Matteo)

Kimberly visiting Kevin before the pandemic. (Photo courtesy Kimberly Matteo)

Department officials affirm that their efforts to manage COVID-19 inside the state’s prisons have been effective. But testimonials from inmates paint a less rosy picture.

“When it suddenly became apparent that we were having issues, I was in a unit with a lot of older guys,” said Carl Schumann, who was released from Sterling on May 14. “We didn’t start getting tested until around May 5. Check the news. Cases were being reported daily at Sterling for weeks prior to us even getting tested.”

Schumann describes solitairy confinement or "the hole" being used as a method of quarantining.

Schumann recalled a time when his cellmate tested positive.

“They moved him to an all positive unit and us to an all negative unit. Now there were about six guys that tested inconclusive and they were brought to the negative side instead of keeping them somewhere until it was confirmed. The unit that tested negative with those inconclusive guys were the ones bringing food to us who were quarantined. Well, cases in my unit rose. The prison spread it themselves. When I left there were 400 cases,” said Schumann.

“Social distancing was impossible,” he continued. “Two in a room, shared bathroom — there’s no getting away.”

Neither was Schumann impressed with the hygiene measures he encountered at Sterling.

“They gave us two masks that we had to wash out, obviously with the same sinks. I was never even given sanitizer.”

Carl Schumann a few weeks after his release from the Sterling prison on May 14, 2020. (Carlos Monkus, CU News Corps)

Carl Schumann a few weeks after his release from the Sterling prison on May 14, 2020. (Carlos Monkus, CU News Corps)

Inmates are sometimes quarantined in cells that have been used for solitary confinement, making them reluctant to report exposure.

Over two weeks in March, Jason Higdon was quarantined alone in a cell at Centennial without his ADHD medication for 23 hours a day. The experience strained his mental health to the point that he had trouble remembering all of it.

“It’s kind of a blur, to be honest,” he said. “I couldn’t really function.”

Jason Higdon a few weeks before his early August imprisonment. (Carlos Monkus, CU News Corps)

Jason Higdon a few weeks before his early August imprisonment. (Carlos Monkus, CU News Corps)

Helen Griffiths pointed out the danger. “There are real concerns that people won’t report when they have symptoms when they know that they’ll be put in solitary,” she said.

Colorado abrogated solitary confinement (which the state calls administrative segregation) in 2017.

Amaral explains what happened when inmates tested positive.

“A few years ago, they got rid of administrative segregation, the 23-hour lockdown. Brutal. Not the way to go about it,” said Eric Shaffer, Department of Corrections liaison for Colorado WINS, a union representing state employees.

But the abrogation applied only to administrative segregation lasting more than 15 days. Rick Raemisch, the Department’s executive director at the time, wrote a memo lauding his decision to abolish “long-term” isolation: “Keeping someone in solitary confinement for over 15 days is torture.” Up to 15 days in isolation, his reasoning went, was perfectly acceptable.

Prison staff have confirmed that following COVID-19 safety guidelines, especially in regard to social distancing, often proves impossible.

“If there’s an altercation, all of that is out the window,” said Shaffer. As their union representative, he often hears corrections officers express their concern about the futility of maintaining pandemic protocols while carrying out many of their regular duties.

“One of my guys was tasked with trying to resuscitate an offender who had committed suicide,” he added.

Although the problem of overcrowding in Colorado prisons is well known, less attention has been paid to the problem of understaffing. “These places are running at or below minimum staffing levels, and even with the recent pay raise there’s still high turnover,” said Shaffer.

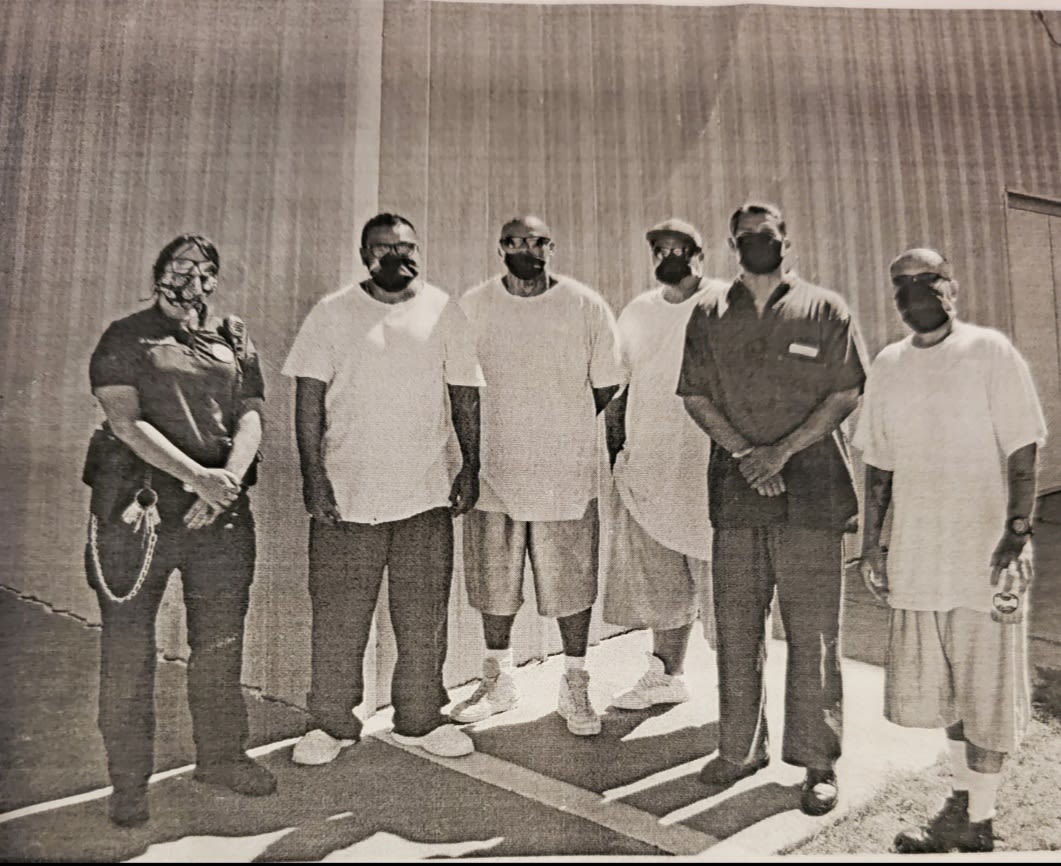

Amaral stands with inmates who worked as a cleaning crew during the initial outbreak. (Courtesy Jamie Amaral)

Amaral stands with inmates who worked as a cleaning crew during the initial outbreak. (Courtesy Jamie Amaral)

That can make COVID-19 regulations difficult to enforce. “You might have one guy per 150 offenders in some cases,” said Shaffer. “Staff are getting exhausted, working double and triple shifts — and that creates a danger.”

Jamie Amaral was a sergeant at Sterling until she resigned in September. She felt that the callous way some of her colleagues treated inmates was putting their lives at risk. She recalled the first day the facility locked down in response to the pandemic, when she was tasked with supervising a team of officers delivering food in carts to inmates in their cells.

“I made clear requests of the staff to follow orders to prevent contamination and most of them went rogue. This was how things would go for the next few months until I resigned,” she said.

Amaral held 87-year-old David Grosse’s hand as he died from COVID-19 in May. It was her breaking point.

Amaral's Sterling guard memorabilia. (Photo courtesy Jamie Amaral)

Amaral's Sterling guard memorabilia. (Photo courtesy Jamie Amaral)

Prison staff are the only people who move in and out of prisons every day, making them the most likely ones to carry the virus inside. Given that, Shaffer feels it takes too long for staff to get test results back.

“There have been cases where I’ve been told it’s a week. I think honestly the state should invest in a way so that tests are processed more quickly,” he said.

The ACLU of Colorado brought a lawsuit in May against the Department seeking to compel its release of prisoners who are at risk of developing severe symptoms if infected with COVID-19. The ACLU included prisoners older than 55 among those it classified as especially vulnerable to the virus. The parties settled the lawsuit in August, although they have not made its terms public.

“We were concerned because conditions of confinement in Colorado prisons are ripe for the spread of COVID,” said Griffiths. “You’re living, sleeping, toileting within feet of each other. What was really concerning to us was how so many older, medically vulnerable people still had roommates.”

Prisoners reported their situation did not improve once they left their cells, when they regularly stood shoulder to shoulder waiting in line for the telephone, bathroom, and food in the mess hall.

“The current population of the individual prisons within the Department are such that they would not be able to adhere to any of the CDC guidelines, e.g., standing six feet apart or congregating in numbers fewer than 10,” said Denise Maes, public policy director of the ACLU of Colorado.

“A prison sentence shouldn’t be a death sentence, we were worried it would be for many,” said Griffiths.

Other states have already sought to reduce population density in their prisons by releasing vulnerable inmates en masse. California has designated at least 6,500 prison inmates, including those older than 65 who have chronic conditions, eligible for early release because they are at greater risk for morbidity and mortality should they contract COVID-19. The state freed 2,345 inmates early in July. Although data has not yet been collected, nothing indicates that the move has led to an increase in the incidence of crime.

Griffiths was confident that older and other medically vulnerable prisoners pose no significant public safety risk. “Anthony Martinez could safely and easily be reunited with his family,” she said.

Richard van Wickler, retired warden, agreed. “Their case should be reviewed if they aren't a hazard to public safety and they aren’t the same person they were when they committed their crime — and who is after 30 years? At that point, we’re punishing them because we’re mad at them, not because they need punishment.”

Griffiths said adjustments the Department could make to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in its prisons, such as providing more masks or better access to hygiene products, would be inadequate. “Those are just band-aid solutions to what really is the chronic issue, which is that there are just too many people behind bars.”

The mass early release of inmates into Colorado communities would certainly present challenges. That the Department does not have the pandemic under control in its prisons is evidenced by the extremes it has gone to.

“Legal counsel can’t even come in,” said Shaffer.

“We were about to open visitation back up. Then we get one person positive, and we test everyone, now we wonder what to do. It would be a disaster to have another outbreak while we have visitation open,” said Dean Williams, the Department’s executive director, at the Oct. 8 meeting. “We don’t start visitation under any sky unless our confidence level is 90%.”

Political constraints will doubtless continue to dog initiatives to free the state’s vulnerable inmates. Colorado Governor Jared Polis signed an executive order relaxing standards around early release in March. He allowed the order to expire in May, however, after Cornelius Haney was arrested on suspicion of murder two weeks after being released early from prison because of concerns over COVID-19.

If more than a thousand elderly Colorado inmates were released from prison, they might be heading from the frying pan into the fire. COVID-19 has killed at least 824 residents and staff at Colorado nursing homes.

Williams acknowledged that moving them anywhere is risky.

“California moved some prisoners under medical advice from a prison that had had a large outbreak, moved some 60-70 prisoners there, resulting in a massive outbreak,” said Williams, referring to the deadly outbreak that struck San Quentin State Prison in August. “Over 2,000 men became impacted by that decision. You have to live with those decisions.”

Shaffer recognized the difficulties the Department has faced. “They’ve done a better job than other states,” he said. “I’ll give the Department credit. Director Williams is a pretty good guy.”

At the Oct. 8 meeting, Williams seemed to show genuine compassion for Colorado’s prisoners and their families. “We try to lead with courage,” he said.

Back in her kitchen, Kelly Brasier sipped her tea and thought about her Uncle Anthony. She thought about whom she would call and write to that day as she continued her fight to bring her uncle home. And she thought about how she would wait for him to call, ready to seize a precious chance to talk to him for maybe the final time.

Kelly Brasier sipping her tea, pondering her uncle's fate, in early Nov 2020 (Photo courtesy Cody Brasier)

Kelly Brasier sipping her tea, pondering her uncle's fate, in early Nov 2020 (Photo courtesy Cody Brasier)

Brasier often asks herself what more can be done to keep her uncle and others in his position safe.

For Griffiths, the answer is simple: “The only solution is reducing the number of people in prison.”